University of Richmond undergrads are changing brain research

Fighting back against depression and dementia

Rats are driving cars in Dr. Kelly Lambert’s Behavioral Neuroscience research lab at the University of Richmond. For them, the reward is Froot Loops. For neuroscience, the payoff is far sweeter.

While this literal rat race may seem "on the level of pigs flying," in Lambert’s words, the research is showing how the brain can continue to grow and evolve throughout life, with the right stimulation or, in the case of the rat lab, enriched environments. Examples of those enrichments include enclosures with plastic toys and ladders or items found in nature, like sticks and pinecones.

The findings could lead to cures for everything from depression to dementia or even paralysis.

"The brain is an organ. It's not magic. It's not mystical. We need to treat it like that," says Lambert. "Deaths related to cardiovascular disease; they've gone down. AIDS has gone down. Cancer has gone down, but depression rates have just skyrocketed. That’s unacceptable."

She says it’s time we look at "behaviorceuticals," a term she coined, to highlight the importance of changing behaviors, environments, and lifestyles to facilitate an improvement in mood or neuroplasticity (the brain’s ability to change over time). In addition to her peers in science, Lambert’s work has caught the attention of national media and television producers, who have featured the rats on the Netflix show, "The Hidden Lives of Pets."

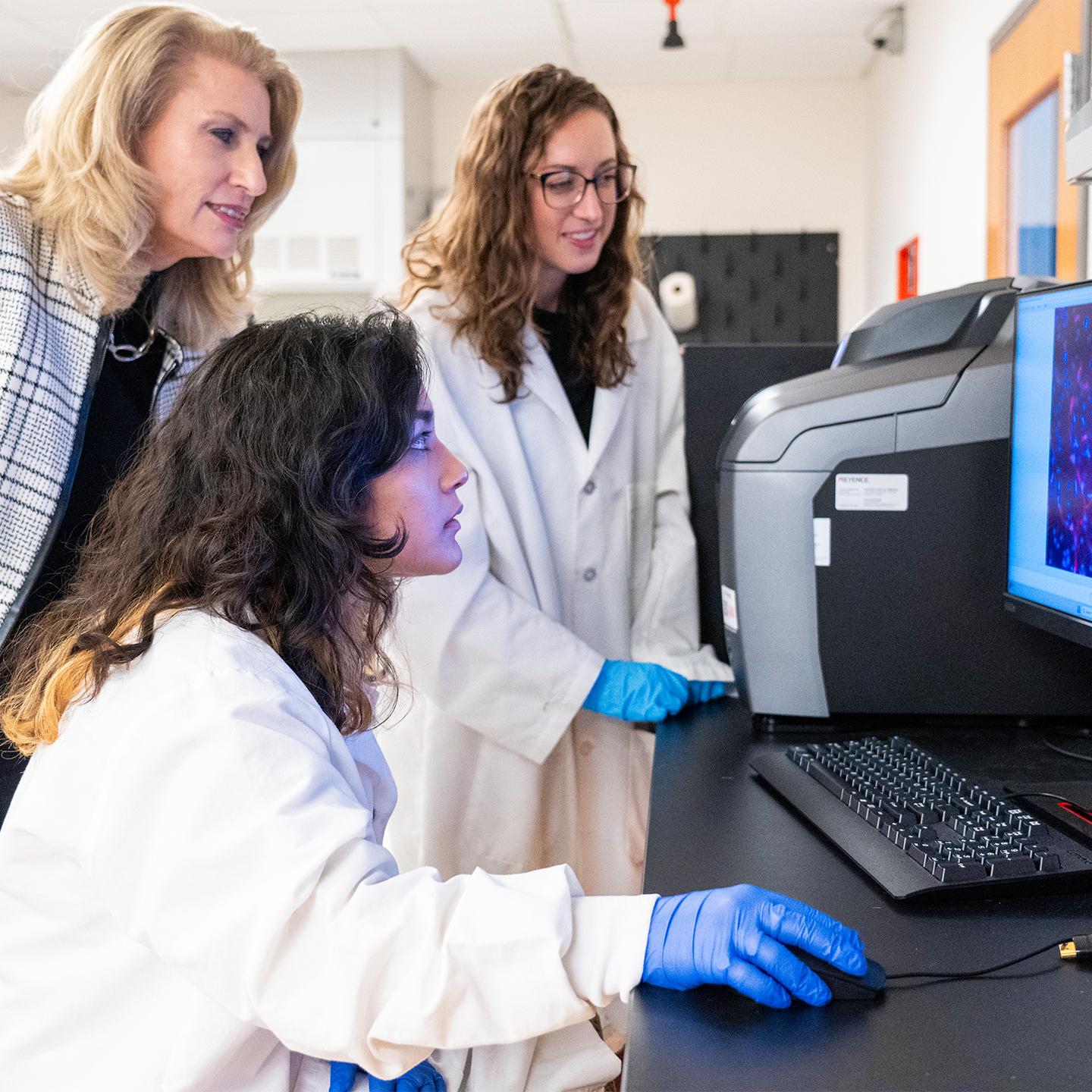

What’s even more remarkable than the rats driving the cars is the makeup of the team driving the research. It consists of Lambert and University of Richmond undergraduates from across disciplines. She calls them "Lambert’s Labsters."

While the rodents are undoubtedly contributing to science and the future of healthcare, they’re also the centerpiece of a type of student-faculty mentorship felt long after students leave the University of Richmond campus. It’s a powerful blend of passion and pedagogy.

The brain is an organ. It’s not magic. It’s not mystical. We need to treat it like that.

Neuroscience Program Co-coordinator

A Seat at The Table

"I did mention Dr. Lambert in my application to the University of Richmond," says Paen Luby, a junior computer science and psychology major. "One of the first questions I asked her was, 'Do you think you could use a computer scientist in your lab?'"

Luby became interested in neuroscience in high school, when her grandmother suffered a stroke, and the family was not allowed to make frequent visits to see her due to COVID protocols. Luby found out about Lambert’s research on the brain through a TEDx talk online.

"Where is this woman from?" Luby thought.

Luby chose Richmond for the research and for Lambert, with the hope that she could be integrated into the program. Lambert, in turn, made a space for Luby that didn’t originally exist through Brain-Machine Interface.

It has added a new technological element to the lab, while giving Luby a sense of belonging and an opportunity to play to her strengths.

"I’m in two research labs here," adds Luby, who has also started a computer science club called Girls Who Code. "I have basically used every funding resource that the school has given me."

Izzy Dilandro was part of Lambert’s wild rat research. The Richmond junior says she didn’t initially want to study math or science in college, but that all changed after taking Behavioral Neuroscience with Dr. Lambert.

"I think all it took was having someone to teach me, that made it more accessible," Dilandro says. "It definitely opened up an entirely different career path, and now I think I want to go on to get a Ph.D."

Oh, The Places They’ll Go

Dr. Lambert says she ends up learning just as much from her students as they learn from her. At the start of the semester, she invites them to write a bio sketch about themselves, so she can learn their interests and passions.

Once a semester is underway, she assigns reading content before each class, along with talking points, asking students to reflect and write down what bits of information they found most interesting. Lambert believes students are more likely to participate in discussions once they’ve written out their thoughts.

She also spends a lot of time finding quirky stories to support her subject matter. Lambert says quirky is what the brain likes, and it helps students retain the information.

Perhaps one of the most interesting teaching methods Lambert incorporates is the art of the unexpected. For example, Lambert has assigned self-paced juggling lessons to demonstrate the neuroplasticity of learning a new skill. Or she gives students an opportunity to take a "leap of faith" from a rock wall onto a small trapeze bar to raise and test their stress-hormone response.

"Students are amazed to see they had a higher stress level in their saliva when giving a class presentation than when seemingly jumping off a cliff," says Lambert.

Lambert describes her teaching style as challenging but nurturing. She believes work in the classroom or lab should be difficult but reasonable, and it should leave students with a sense of accomplishment.

Lambert embraces the influence she has with her students — whether it’s helping prepare them for future careers or even reminding them to take advantage of being at the nation’s No. 1 Most Beautiful Campus (The Princeton Review).

"I’m their brain coach," says Lambert. "I tell them all the time, [the UR campus] is one of the most enriched environments. Take a walk around the lake, take advantage of the beautiful landscape and all the different offerings. Go have some fun."

Her approach to education and research has not gone unnoticed. Lambert recently won the SfN Science Educator Award and earned a spot as a finalist for the Cherry Award. Perhaps her biggest reward is the bond she continues to have with many of the students from her 35 years in higher education. In many cases, she’s attended or even directed their weddings. In many others, she has cheered alongside as they have gone on to become trailblazers themselves in the career fields of medicine, pharmaceuticals, and behavioral neuroscience.

"My students, they’re going to be the future," she says. "They’re certainly my legacy."

My students, they’re going to be the future. They’re certainly my legacy.